|

| Praise the Lord |

After a slightly more comfortable (and cheaper) ride back to Jorhat from the ghats, this time by bus, we set about exploring the city. It was, and still is, a major centre for exporting chai around India and beyond with the land surrounding the urban sprawl consisting entirely of flat expanses of paddy and immaculately manicured tea gardens.

With the finding of an STD (an abbreviation of ‘standard calls’ I’ll have you know) we manage to get hold of our acquaintances we met at Wild Grass, Puja and Dhruv. We emailed them the week before and told them we would love to take them up on their offer of a base in Jorhat to stay and relax, but were completely unsure what to expect. We were pleasantly surprised. In fact, we were more than that… We had hit the jackpot.

Dhruv came and grabbed us in his big old 4x4 and drove us to their pad on the outskirts of town- a beautiful little house. We were welcomed by a beaming Puja who showed us to our en-suite (we had a water heater and shower!!!) room (we had a double bed!!) and then shepherded us to the table for lunch.

We discussed our plans about going to Nagaland and were told theirs. Puja and Dhruv described their work with human-elephant conflict and told us they had a meeting with some affected tribal weavers near Nimiri National Park on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, would we like to come? We couldn’t say no.

After leaving relatively early, with various stops en-route (including a hilarious blagged cup of tea at a safari resort gagging for white tourists), we crossed the vast river around lunchtime and hurtled through Tezpur. The military presence grew steadily the closer we got to Arunachal Pradesh, an independently minded Indian trophy-state with a lot of international borders, which lay only 20 or so kilometers from our destination. Arriving later than anticipated, we headed straight to the meeting. In keeping with most of northeastern India the new faces we met were a real blend of Indian, South-East Asian, oriental and Mongloid. They represented a number of tribal communities living on the periphery of the National Park, including Mising, Assamese, Bodo and Gura.

Our friends’ work here revolved around supporting traditional skills and marketing it to a modern audience in order to encourage alternative income aside from agriculture. This all boiled down to the people and their hungry neighbours- Nelly.

Our residence for the next few days was at a low-key, family run community centre called Dask (I never quite found out what it stood for), our room was in a modernised-take on a traditional Mising home. Bliss.

Over an extremely late lunch we discussed the elephant issue in more depth and learnt about Dhruv’s career as a tracker and elephant conservationist; specializing in this human conflict. The stories we heard were shocking and the negative impact on these poor, rural communities were multi-faceted. The elephants would come out of the park and gorge on the highly evolved, highly nutritious food source they found all around them- rice. Anything or anyone unfortunate to spook one of these goliaths during their nightly raids would feel their wrath. People were regularly killed.

As their forest home decreased, the elephants’ natural food also decreased- increasing the tendency for these giants to cross the small river to venture out and feed on the paddy fields surrounding the village. Where we were staying was right on the front lines. As night fell Dhruv said we may be (un)lucky to experience a raid, the paddy fields were metres away; we laughed nervously, half hoping, half terrified.

A gunshot echoed through the darkness. Some shouting. Then another. It all sounded uncomfortably close. Dhruv jumped up and ran to the car- we were told to stay where we were. He started the engine and began rapidly reversing out of the drive. We held our breath, peering into the empty blackness.

Some raised voices broke the silence and a figure came shambling towards us.

The ‘elephant’ didn’t look sober. The drunk bloke stumbled towards us and slurred an introduction. We all breathed out and relaxed. This was going to be an interesting night.

An hour or so passed before a new disturbance caught our attention. There was a light 100m away… and some singing! Me and Amiee jumped at the chance to experience an impromptu Mising musical session. We arrived at the edge of the small farmstead where the large group of men, women and children were gathered and a pang of recognition hit us. This tune definitely sounded familiar. They finished and started a new song. The men were playing drums and a guitar, the women singing and the children dancing- all in distinct Mising tradition. But the words betrayed their real purpose “We wish you a mewwee ch-wismas, we wish you a mewwee ch-wismas, we wish you a mewwee ch-wismas and a happy noooow yar!”

After a group prayer, the pastor introduced himself and explained they were going between the 18 christian families in the village… caroling. They excitedly offered to come to Dask and we accepted, slightly bemused.

They played a few carols translated into the local language and a few good ol’ traditional numbers. It all culminated in another group prayer and then a handshake and personal message of festive greetings by each of the thirty strong group. They disappeared into the night, their sounds drifting through the air long after we had disappeared to our rooms and collapsed. Exhausted.

The next morning we awoke early and headed into the park for our ‘on-foot safari’, we met our guard/guide and headed down a peaceful tree lined track just as the sun was rising. We crossed the small river by canoe and headed into the park-proper. The guard instantly became alert once we entered the dense forest, his ancient bolt action rifle always at the ready. At every vegetational rustle he would swing it off his shoulder and assume position. We spooked a group of deer, watched a small group of Asian short-clawed otters playfully bounce around a stream and then bimbled back out.

We spent the evening sat around a fire listening to an elderly villager teach us the ways of building a Mising house. His voice was a subtle mix between gravel and satin, his wrinkles etched his face like glacial crevasses, in the glow of the fire, under the painted night sky- his stories were mesmerizing.

We left the north bank, relaxed for a day in Jorhat, then took our bus to Nagaland.

After two local buses and another change on the border, we started bumping, bouncing and climbing into the Naga Hills. Some four hours later, as night was descending, we arrived in the hilltop town of Mon; the capital of this district of Nagaland.

We scurried around and eventually found a guesthouse through the assistance of some friendly local teens. We settled into our room, had some dinner then stood on our balcony and drank in the scene. This was like no town we had ever experienced before. The best description would not give justice to the precariously perched collection of traditional thatched, bamboo Naga long-houses, set beside the occasional concrete church, hospital or school. The roads wound up and down the hill slopes in a dizzying maze, many leading to the ‘Mother’ church on the central, highest peak.

We woke early the following morning and met the DC (district commissioner); a fiery middle aged woman who we instantly liked. She plied us with gifts, whilst simultaneously dressing Amiee in the traditional metkla (skirt) and shawl. She informed us it was Sunday, so we should accompany her to church. We obliged.

The cold, draughty concrete building stood like a monument to Westernization. We joined them for their service, followed by tea then headed to Miss Angua’s administrator’s house, who would apparently serve as our guide.

Sinwang is the son of one of the founders of Mon- the man who put an end to head hunting in the district. A likeable guy, with a calm manner. We told him our plans and he made the arrangements.

The following day, we headed to Lungwa, a village made infamous by it’s opium addicted king and its position right on the Burmese border. The drive was incredible, through timeless villages and along precariously positioned roads.

We were summoned to the top of the hill and registered our presence, then made our way next door to visit the Angh’s residence. The gloomy halls were lined with mithen (feral buffalo) skulls and unfathomable wood carvings. We entered a small room (situated across the border in Myanmar apparently) and met the king. He greeted us, in his leopard-print hat and waistcoat, and offered us a seat. We watched as his aid got out his spoon and started preparing the opium.

After twenty uncomfortable minutes watching this collection of old bloke get wasted, we slipped the king the obligatory 200rps (for his next fix) and left, a bit bewildered. We shuffled past the lines of traders flogging their Naga ancestry, knickknacks and tourist tack situated outside the longhall and made our way down into the village. The pastor showed us around, but he wasn’t that keen to go into much depth.

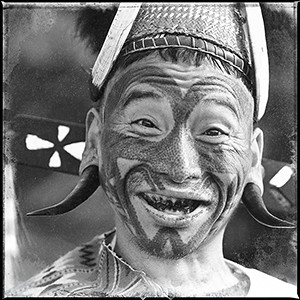

As our spirits dropped we noticed a commotion up ahead and went to investigate. It was Sinwang’s cousin, an artist from London, setting up quite a strange scene. He was positioning an ancient tattooed Naga man into a chair with a head clamp. Timsu greeted us and explained his project. He was making an exhibition where he would film a bunch of Naga elders telling stories, singing or saying poetry, then make plaster moulds of their torso and heads to project the image of them speaking onto the bust.

We watched, spellbound as this frail gentleman started his tale. The passion and conviction in his voice snared us completely. It was an incredible sight.

We left Lungwa as the sun was setting over the Naga Hills, spewing pinks, purples and oranges across the endless forests.

We traveled with Timsu the following day to another village and helped him repeat the procedure. This time, his subject was the last tattooed Angh of Mon district- our host for the next couple of days.

He completed his filming and casting, to much amusement of the gathered crowds and left. We were alone.

Well that’s, not quite true, we were the only foreigners for miles, but we were surrounded by amazingly kind, hospitable people. We all sat round the fire and drank rum with the collection of elderly chaps long into the night, breaking the flimsy barrier of language easily. After a late night visit to the local blacksmith, we hit the hay.

The following day, we visited the blacksmith again. After seeing the objects he makes (including the famed muzzle loaded rifles), we asked him to make us a knife. He skillfully obliged.

Good Post

ReplyDeleteAimee! Good to hear from you! Have you received my email? I sent one to your yahoo address... with photo's! x

ReplyDelete